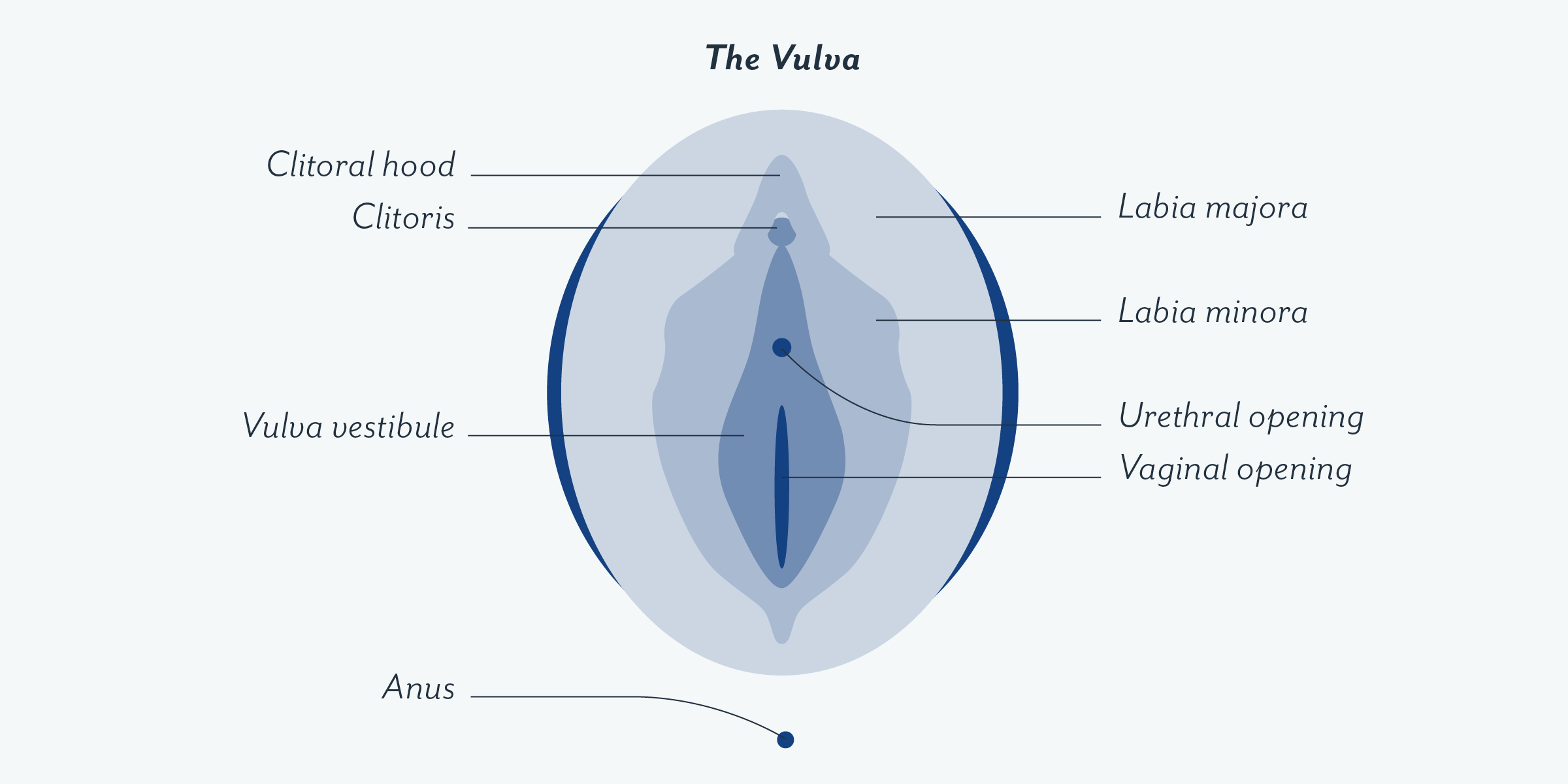

People often use the term vagina to refer to the entire female genital region between the legs—but this is incorrect.

Let’s first start with correcting this terminology. The vulva is the correct name for the external parts of the female genitalia. This includes the glans clitoris , labia minora and majora , opening of the urethra and vagina (the introitus), and the surrounding tissue.

What is a vagina?

The vagina is the tube between the vulva and the cervix . This tube is the connection between your uterus and the outside world. The vagina is what babies exit through during birth, and where menstrual blood exits through during your period. The vagina is also used for insertion, such as with a penis, fingers, female condoms, sex toys, tampons, or menstrual cups .

The vagina can also act as a route to other parts of the body. During penis-vagina sex, ejaculate is deposited in the vagina, allowing sperm to enter the uterus through the cervix. The walls of the vagina can also be used as an administrative route for medications and contraceptives, such as intervaginal hormone creams, the hormonal vaginal contraceptive ring, or vaginal suppository medications.

Anatomy of the vagina

It may seem strange that an organ capable of passing an entire baby through it is also capable of holding a small tampon in place for hours. How does that tampon stay in there? If the vagina is just a tube, shouldn’t the tampon fall out?

The vagina anatomy is much more than just a tube. When it is in a relaxed state (not aroused), the walls of the vagina are collapsed against each other, flattened by the pressure of the surrounding organs and tissues within the pelvis. During this state, a cross-section of the vaginal canal (the vaginal lumen ) can resemble an “H” or a “W” shape, as the walls flatten against themselves (2). From the sides, the vagina offers movable support and pressure, which allow your tampon to stay in place (2,3).

The walls of the vagina are covered by many folds called rugae (3). The walls and folds of the vagina have many purposes, providing both a barrier and access route between the cervix and the outside world. All of these folds allow the vagina to be stretched and expand like an accordion when pressure is applied to the sides (like when a baby’s head is passing through).

The walls of the vagina are composed of different layers of tissue. The surface layers of the vaginal wall are made of mucosal tissue—similar to the tissue that lines your mouth, nose, and digestive tract. Underneath the mucosal tissue are layers of smooth muscle tissue, collagen, and elastin fibers, which gives vagina anatomy both structure and ability to stretch (4).

Fluids are released through the walls of the vagina to keep the area moist, and during times of sexual arousal, to increase lubrication. The vagina is also capable of absorbing some substances—such as medications, hormonal creams, or contraceptives—into the body (3).

How the vagina changes with age

The vagina can change a lot throughout a person’s life (1,5). An average adult vagina is slightly curved, and can range between 7 to 12 cm in length (1,3,4)—but every body is different, and there’s no such thing as a too small or too large vagina.

The vagina is strongly influenced by hormonal changes throughout the body. During the reproductive years after menarche (the first menstrual period) and before menopause , more layers of tissue are present lining the vagina, due to stimulation from higher estrogen levels in the body (3).

The vagina is also influenced by changing hormone levels during pregnancy . Increased blood flow is directed to the pelvis, causing a deeper color change to the vulva and vagina (5). Throughout a pregnancy, the connective tissue of the vaginal walls progressively relaxes, in preparation for the delivery of a baby (5). After delivery, the vagina and vaginal opening temporarily widen, but 6-12 weeks post-delivery, the vagina returns to its pre-pregnancy size (5).

Pregnancy, Birth & Postpartum

Sex, fertility, and contraception after birth

If you’re not sure how long to wait to have sex after…

by Barbara Santen

As people age, the walls of the vagina become more relaxed, and the diameter of the vagina becomes wider (1). When it comes to sexual satisfaction, vaginal size does not affect sexual function (6). The perception of vaginal tightness during sex is primarily related to the pelvic floor muscles, which are present around the base of the vagina and not actually how wide the vaginal canal is.

After menopause, when estrogen is lower, the walls of the vagina become thinner and frailer, which can cause symptoms of vaginal dryness and decreased vaginal secretions (5). This may result in discomfort during sex and increase the chances of vaginal irritation or infection (5).

How the vagina changes during the menstrual cycle

The vagina also changes in response to hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle. Around mid-cycle, when estrogen is highest, vaginal tissue becomes thicker and fuller (5).

The cervix, at the top of the vagina, moves and changes shape throughout the cycle. Before and after the fertile window, the cervix is low and can be felt in the vagina, with a firm texture, and the hole in the center of the cervix is closed. During the fertile window, the hole in the cervix opens to facilitate the entrance of sperm into the uterus (7), the cervix rises higher in the vagina, and is softer when touched (8).

It seems like you might be referring to aspects of female anatomy, particularly the external and internal structures of the vagina. Below is an essay exploring the structure and function of the vagina, including its surrounding anatomy and misconceptions about it.

Understanding the Anatomy and Function of the Vagina

Introduction

The female reproductive system is a complex structure designed for various functions, including reproduction, sexual pleasure, and childbirth. Among its key components, the vagina plays a central role, but it is often misunderstood due to cultural myths and lack of education. Some misconceptions exist regarding the structure of the vagina, including the idea that it has “legs” or rigid divisions. In reality, the vagina is a muscular canal, and its surrounding structures, such as the labia, pelvic floor muscles, and vaginal walls, contribute to its function. This essay explores the anatomy of the vagina, its role in the female body, and the myths surrounding it.

Anatomy of the Vagina and Surrounding Structures

The vagina is an elastic, muscular canal that connects the external genitalia to the cervix, which leads to the uterus. It is part of a larger reproductive system that includes both external and internal structures.

External Structures

Internal Structures

The Function of the Vagina

The vagina serves several key functions in the female body:

Common Myths and Misconceptions

1. “The Vagina Has Legs”

There is no anatomical basis for the idea that the vagina has “legs.” However, the clitoral legs (crura), which extend from the clitoris internally, might be the source of this misunderstanding. Additionally, the pelvic floor muscles that surround and support the vagina contribute to its function, but they do not resemble “legs.”

2. “The Vagina is Always Tight or Loose”

The vagina is a flexible organ that naturally expands and contracts. It does not permanently “loosen” after sexual activity or childbirth, as muscles can regain tone with time and exercise.

3. “Virginity Can Be Proven by Examining the Vagina”

There is no medical way to determine virginity. The hymen (a thin membrane at the vaginal opening) can stretch or tear for many reasons unrelated to sex, such as exercise, tampon use, or medical exams. The idea that a woman’s body changes in a visible way after losing virginity is a myth.

Conclusion

The vagina is an essential and highly adaptable part of the female body, playing key roles in reproduction, menstruation, and sexual health. Despite its importance, many misconceptions persist about its structure and function. The idea that the vagina has “legs” is anatomically incorrect, though certain internal structures, such as the clitoral crura and pelvic floor muscles, contribute to its support and function. By improving education on female anatomy, society can dispel myths and promote a more accurate understanding of women’s bodies.